1. South African electricity sector overview

This section gives an overview of the South African electricity market and provides foundational information needed to explore the investment opportunities in the South African clean energy sector.

1.1 South African electricity landscape

South Africa’s electricity supply is dominated by coal-fired power generation (Figure 1). These power stations are primarily owned and operated by Eskom, the national power utility. A minority of the power demand is met through municipalities, imports, and independent power producers.

Figure 1: Electricity contribution by source

Sources: Eskom, 2023.

1.1.1 Rolling blackouts

Historical supply and demand imbalance in South Africa’s single buyer electricity model resulted in intensive rolling blackouts (locally referred to as ‘loadshedding’) countrywide. Rolling blackouts are classified into ‘stages’, with each stage representing a gigawatt of electricity demand that is required to go offline to match electricity supply with demand. Figure 2 provides an overview of the stages implemented and total energy consumption reduction incurred for each year since the first loadshedding started in 2007. Data are collected and shared by EskomSePush (ESP).

Figure 2: Loadshedding by stage (2018 – 2023)

Source: EskomSePush, 2023.

Loadshedding has intensified over recent years due to the degradation of Eskom’s coal fleet, illustrated through their Energy Availability Factor (EAF) (Figure 3). Many of Eskom’s coal power plants have reached their design end-of-life and are becoming less reliable and prone to breakdowns. Eskom’s board of directors, appointed in 2022, were mandated by the then Minister of Public Enterprises, Pravin Gordhan, to achieve an EAF of 75%.

Figure 3: EAF for Eskom power plants (2017 – 2023)

Source: Eskom, 2023

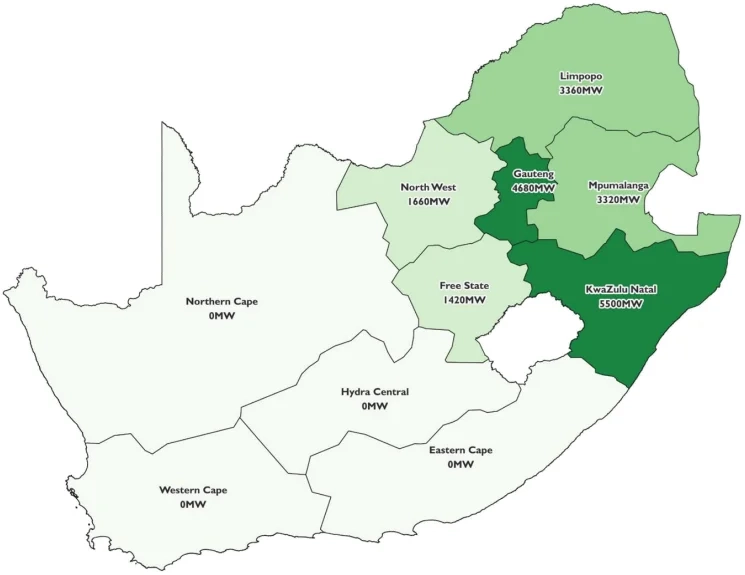

1.1.2 Grid constraints

Following the rollout of the Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement Programme (REIPPPP) Bid Window 6 (BW6), it became apparent that there is no more grid capacity available in key areas for connecting new generation projects. Eskom confirmed that there is no longer grid capacity available in the Northern Cape, Western Cape, Eastern Cape, and parts of the Free State. New project developments will need to focus on areas with grid capacity that may be in an area with less desirable wind or solar resources. Eskom recently published data on grid capacity.

Figure 4: Eskom generation connection capacity

Source: Eskom, 2023

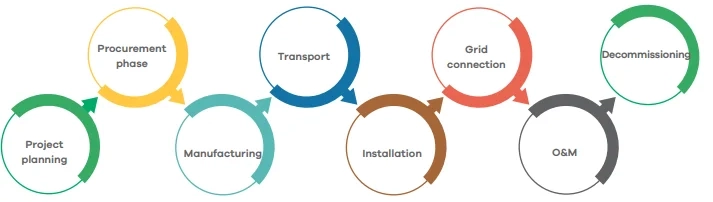

1.2 South Africa’s renewable energy value chain and key players

In South Africa, the global industry players dominate the renewable energy value chain, which has a typical structure as illustrated in Figure 6. With market developments (e.g. reduced profit margins due to decreased tariffs), there has been considerable consolidation in the market globally.

Figure 5: Renewable energy value chain

Source: IRENA, 2017.

South African industry awaits the launch of a new Integrated Resource Plan (IRP), new REIPPPP BWs, the South African Renewable Energy Masterplan, and changes in South Africa’s regulatory environment. The need for local creation is driving the establishment of a local manufacturing base and just transition objectives, including job creation in transition areas.

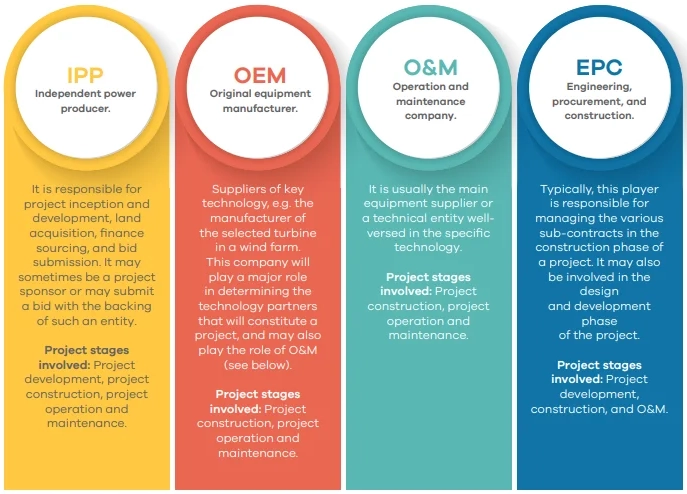

Stakeholders in the large-scale renewable energy industry developed in response to the REIPPPP can be categorized according to the project development phases that the programme follows: development, construction, and operation and maintenance. Accordingly, the key players or company types involved in this market are described in Figure 6, indicating the project development phase in which they are typically involved.

Figure 6: Typical company types involved at different stages of project life

2. Market size

The introduction of renewable energy in South Africa dates to 2003 with the delivery of the 2003 White Paper on Renewable Energy. However, the renewable energy framework only started to take shape in 2010 with the introduction of the IRP (2010-2030). The purpose of the 2010 IRP was to determine the preferred energy mix over the next 20 years. The IRP was intended to be updated regularly, however, only one update occurred in 2019. A new IRP update is being developed but has not yet been released.

2.1 Large-scale renewable energy market size

The REIPPP was established to facilitate the uptake of renewable energy in South Africa, as originally detailed in the 2010 IRP. The Independent Power Producer Office (IPPO) was created to fulfil three specific duties for the REIPPPP, namely professional advisory services, procurement management services, and monitoring, evaluation, and contract management services.

The first REIPPPP project became operational in November 2013. A number of related public programmes followed the REIPPPP including the Risk Mitigation Independent Power Producer Procurement Programme (RMIPPPP) and Battery Energy Storage Independent Power Producer Procurement Programme (BESIPPPP). The RMIPPPP aims to fill the current short-term supply gap, alleviate the current electricity supply constraints, and reduce the extensive utilization of diesel-based peaking electrical generators. The BESIPPPP aims to increase the available grid capacity in constrained regions, such as the Northern Cape, which will allow more generation capacity to be connected. The progress of the bid rounds is summarized from the IPPO report, in the Table 1.

Table 1: Progress of bid rounds (years)

Source: IPPO, 2024

The private sector has witnessed a notable surge in both the total number of projects and their overall capacity. In 2021, the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (DMRE) made amendments to Schedule 2 of the Energy Regulation Act, Act 4 of 2006 (ERA). This revision resulted in a substantial elevation of the licensing exception for connecting power generators, increasing the limit from 10 MW to 100 MW. However, in the upcoming 2023 amendment (pending final approval), the exception is slated for removal, thereby eliminating capacity constraints for privately developed generation projects seeking grid connection. The removal of a substantial regulatory impediment has empowered the initiation of new and private renewable energy projects. Consequently, there has been a marked expansion in the realm of large-scale private offtaker agreements. The National Energy Regulator of South Africa (NERSA) publishes a comprehensive list of registered private projects, providing transparency and accountability in this dynamic landscape (see Figure 7).

Figure 7: Projects registered with NERSA

Source: NERSA, 2024

The future market size of large-scale renewable energy projects is uncertain, with changes to the projections occurring every few years. Despite this uncertainty, key planning organisations predict a large amount of growth. Figure 8 shows the projections from different sources for new renewable energy projects and grid storage projects.

Figure 8: Renewable energy capacity projections

Sources: DMRE 2019; Eskom 2023; Eskom, the South African Photovoltaic Industry Association, and the South African Wind Energy Association 2023

The renewable energy projections in Figure 8 are summarized from three different sources. The 2019 IRP update focussed on the government-planned energy production and storage capacities. Its implementation for government projects are limited to the ministerial determinations, but private project growth has escalated. However, since the transmission of electricity will be done through Eskom’s new subsidiary, the National Transmission Company of South Africa, all projects need to be accommodated through long-term grid planning that considers the existing grid constraints. Eskom’s Transmission Development Plan (TDP2023) therefore provides insights into the grid capacity constraints and renewable energy connection capabilities. A separate grid survey was conducted in partnership between Eskom, the South African Photovoltaic Industry Association and the South African Wind Energy Association, which provided insights into the areas, technologies, and statuses of new renewable energy projects that the large-scale renewable energy industry is focussing their resources on. Many of these projects will not materialize, but the survey nevertheless provides insights into the capacity demand from industry for new developments.

3. Policy and regulation

This section provides an overview of key policy regulations that impact the large-scale renewable energy and energy storage market.

3.1 Governing bodies

There are a large number of government entities involved in developing and implementing policies, plans, and programmes for the electricity sector. The most prominent of these are listed in Table 2 below.

Table 2: Prominent government bodies involved in governing the electricity sector

3.2 Local policies

There are various local policies and regulations that recently changed or in the process of changing, which will have a significant impact on the large-scale renewable energy market (Table 3).

Table 3: Policies and regulations that impact the large-scale renewable energy market

Sources: As found in hyperlinks

3.3 International policies

International trade has a large impact on the export driven manufacturing companies. South Africa’s renewable energy market is not large enough to support specialized renewable energy component manufacturing facilities for key equipment, such as wind blades gearboxes, making component manufacturers either uncompetitive with imported equipment or dependent on government support. Favourable access to international markets will increase the attractiveness of investing into manufacturing in South Africa. Some of the most impactful international policies are listed in Table 4.

Table 4: International policies that impact the large-scale renewable sector

Further to this, the dtic provides a list of trade agreements, available from their website (dtic 2024).

References

- Department of Mineral Resources and Energy 2019. Integrated Resource Plan 2019. Pretoria, South African Government. Available from <https://www.energy.gov.za/irp/2019/IRP-2019.pdf> [Accessed date]

- Department of Trade, Industry and Competition 2024. Trade Agreements. Pretoria, South African Government. Available from http://www.thedtic.gov.za/sectors-and-services-2/1-4-2-trade-and-export/market-access/trade-agreements/ [Accessed date]

- Electricity Regulation Act 4 of 2006.

- Eskom 2023. Transmission Development Plans. Sandton, Eskom. Available from https://www.eskom.co.za/eskom-divisions/tx/transmission-development-plans/ [Accessed date]

- Eskom 2024. GCCA 2025 Results. Sandton, Eskom. Available from <https://www.eskom.co.za/eskom-divisions/tx/gcca/gcca-2025/> [Accessed date]

- Eskom, the South African Photovoltaic Industry association, and the South African Wind Energy Association 2023. South Africa Renewable Energy Grid Survey. Sandton, Eskom. Available from https://www.eskom.co.za/eskom-divisions/tx/renewable-energy-grid-survey/ [Accessed date]

- Eskom’s new grid capacity allocation rules

- EskomSePush, 2023. Loadshedding by stage (2018.- 2023). Available from <https://esp.info/> [Accessed date]

- European Commission 2023. Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism. Brussels and Luxembourg, European Commission. Available from <https://taxation-customs.ec.europa.eu/carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism_en> [Accessed 16 January 2024]

- Independent Power Producer Office (IPPO) ??. Specific report (table 1 reference). Pretoria, South African Government. Available from [Accessed date]

- Independent Power Producer Office (IPPO) 2024. Projects. Pretoria, South African Government. Available from <https://www.ipp-projects.co.za/? [Accessed date]

- IRENA 2017. Details. Available from [Accessed date].

- National Energy Regulator of South Africa (NERSA) 2024. Electricity Registration. Pretoria, South African Government. Available from https://www.nersa.org.za/electricity-overview/electricity-registration/ [Accessed date]

- National Treasury. 2022. Preferential Procurement Regulations. Pretoria, South African Government. Available from https://www.treasury.gov.za/legislation/regulations/PREFERENTIAL%20PROCUREMENT%20REGULATIONS,%202022.pdf [Accessed date]

- Nyathi, Mandisa 2022. ‘Eskom’s new board under the whip.’ Mail and Guardian. 28 October 2022. Available from <https://mg.co.za/business/2022-10-28-eskoms-new-board-under-the-whip/> [Accessed date]

- Office of the United States Trade Representative n.d. African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA). Available from https://ustr.gov/issue-areas/trade-development/preference-programs/african-growth-and-opportunity-act-agoa [Accessed date]

- Public Procurement Bill

- The White House 2023. Building a Clean Energy Economy: A Guidebook to the Inflation Reduction Act’s Investments in Clean Energy and Climate

- Action. January 2023, Version 2. Washington, D.C, Government of the United States of America. Available from https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Inflation-Reduction-Act-Guidebook.pdf [Accessed date]