A blog by Nicholas Fordyce, Communications & Publications Manager at GreenCape. Cover image: A recently installed micro-grid in the foreground, dwarfed by the now decommissioned Komati coal plant in the background. Photo: Nicholas Fordyce

“You were going 101km/hr in an 80-zone sir. That’s a R1500 fine.”

Bugger! I was.

“It’s better to get to where you are going the right way, rather than to rush.”

It wasn’t part of my plan to be pulled over by a traffic cop on route to Pestana Kruger Lodge for the International Cleantech Network’s (ICN) annual conference, but a momentary lapse in concentration, as I pondered the ICN delegates’ first impressions of South Africa, had done me in.

Notwithstanding that blip, driving alone had proven a triumph and afforded me a rare opportunity to indulge in five hours of uninterrupted thinking time. I didn’t even play music. Perhaps the only (other) negative from the drive was the endless merry-go-round of passing large trucks, or navigating sections of roadworks. But more on that, later.

During the journey, from South Africa’s economic capital of Johannesburg, through the Highveld and her mine dumps, and then through Mpumalanga’s coal belt, I couldn’t help but wonder about those first impressions. What would our colleagues from overseas be thinking?

Whenever I’m in the Highveld, I’m struck by the big skies we get here. There’s a contradiction I can never quite solve; somehow I feel closer to the sky here than anywhere else, and yet the sky also feels vaster here than almost anywhere else I’ve been. A visitor once commented to me that he felt there “ought to be more than 360 degrees to this place”, and I think he’s right. Maybe it’s a consequence of the flat open grasslands that define the area. Maybe it’s just something that goes back to my childhood.

Regardless, this journey had a unique twist. Perhaps governed by a sharper eye than usual, those enhanced observation skills linked to that familiar panic; we have guests, is the house clean; I couldn’t help but notice something else about the sky: Pollution. Our skies are filthy and It’s impossible to miss.

Image 2: Air quality: Gauteng and Mpumalanga’s air quality is surely deteriorating as our coal-based industry dumps tonnes of carbon monoxide and other noxious gases into our atmosphere. Here a sugar mill, seen from within the Kruger National Park, deposits fumes into the air. Photo: Nicholas Fordyce

My GreenCape colleagues responsible for the arranging the conference programme are either geniuses, or were unintentionally so (and I’m going to assume the former), because kick-starting the conference with a visit to the Eskom-owned Komati Power Station provided a perfect contextual point.

The Komati Power Station was commissioned in 1961 and consisted of nine coal-fired generators, with a total installed capacity of 1 GW – more than twice the capacity of any existing power station in South Africa at that time. According to a PCC report, during the period of full operation, the site fell in breach of the national air quality laws, with Komati granted its first suspension of compliance with the minimum emissions standards in 2014.

If cries for a clean economy from Greta Thunberg and her allies aren’t enough, our skies are now sending a clear message: We MUST transition away from coal.

On the face of it, this should be easy. Recent market intelligence, published by South Africa’s ICN representative GreenCape (in partnership with the Mpumalanga Green Cluster Agency), has revealed a number of significant opportunities in the renewable energy sector for the province. At the utility-scale, there is a potential market size of ~R21.1 billion (up to 2 GW by 2030), whilst at the small-scale, the embedded generation market has a potential total market size of ~R3.2 billion by 2030. The potential market size for the battery energy storage system market is ~R2 billion, also by 2030. These opportunities are not to be sniffed at, and hint that investment into the market should be expected.

There are even apparent solutions for some of the other challenges observed along the journey. Recent industry briefs from GreenCape highlight the growing potential of the cannabis and hemp markets. Of particular interest is the potential for hemp to be grown on disused mine land and dumps, where former mining activities have left the land pretty much unsuitable for anything else. A range of opportunities have already been demonstrated for hemp and cannabis in Cape Town’s pharmaceutical, construction and textile industries; and it seems likely that these opportunities have broader relevance within the context of the country as a whole.

So what’s the hold up. Why can’t we press play and get moving?

A morning drive in the Kruger Park, provides an unexpected metaphor. In the early light, I spot two exquisite African Green Pigeons. A thought suddenly pops into my head. Our cities are filled with urban Feral Pigeons. They are a symbol of our linear, take-make-waste-pollute, economy. The pigeons are the jobs of that economy. There are many of them. How do we redesign our system in such a way that we keep the pigeons along for the ride, but such that they emerge on the other side as their (objectively) better looking green versions?

Image 3: An African Green Pigeon, perhaps a symbol of a green economic future, basks in the early morning light in the Kruger National Park. Image: Nicholas Fordyce

On the final morning of the conference, with new friendships formed, I set off to Komatipoort with two other delegates to run the recently opened Kambaku Golf Course Parkrun (if you’re in the area on a Saturday, give it a go!). Parkrun is an international initiative that started in the UK, but it has taken South Africa by storm, in part, I believe, because of South African’s culture of mass participation. From Malelane to Komatipoort it’s a 40-minute drive, due East, towards the Mozambique border. For about half of that drive, or at least 10 kilometres, we witnessed something rather extraordinary. This time lapse, taken by my colleague Collins Nyamadzawo captures it best; a seemingly never ending line of (mostly) coal containing freight trucks, waiting to cross the border into Mozambique where most of the coal will be exported via Maputo.

Witnessing this line of trucks felt like finding the final piece of a puzzle I had been trying to solve all week. Suddenly our journey from Jo’burg to Kruger, and all the bits accumulated along the way, made sense.

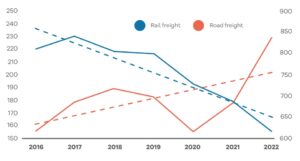

Our coal-based economy is driving us in the wrong direction. Lines of trucks, in the absence of a properly functional (electric) rail system, pump noxious fumes from their exhausts whilst, quite literally, destroying our roads (remember the bit about passing trucks and road works?). GreenCape’s 2024 Electric Vehicles Market Intelligence Report (MIR) highlights the trends in road and rail freight in the country. Road freight in South Africa was deregulated in 1988. This deregulation marked a significant shift in the country’s transport policy, allowing for more competition and efficiency in the road freight industry. Prior to this, the industry was heavily regulated, with strict controls on routes, rates, and entry into the market. The deregulation aimed to reduce transportation costs, improve service quality, and enhance the overall efficiency of freight logistics within the country. This, coupled with subsequent decreased rail infrastructure maintenance and quality of service, has resulted in a sharp decline in rail freight volumes and a steep rise in total road freight volumes. All of this is contributing to deteriorating air quality for the region, and heavily potholed roads.

Image 4: Rail vs. road freight volumes (millions of tonnes) in South Africa over time (Sourced from GreenCape’s 2024 Electric Vehicles MIR and originally from Greyling, 2023).

Komati has now been decommissioned and Eskom has developed a comprehensive Just Energy Transition (JET) strategy which places equal importance on the ‘transition to lower carbon technologies,’ and the ability to do so in a manner that is ‘just’ and sustainable. Formally Eskom employed more than 500 people in full-time jobs at Komati. At the time of decommissioning, accordingly to Eskom, around 375 full-time workers were employed at the plant, with an additional 400 ERI employees and 527 contract workers. Additionally, a multitude of service providers benefitted tangentially from the plant; providing a range of services and, critically, employing a not insignificant number of people; both directly and indirectly.

So much of our economy, good and bad, is still linked to this system. As we drove by the line of trucks outside Komatipoort, we noticed many women, selling fruit to the truck drivers. As is the South African (African?) way, an informal economy has been established to support the network of truck drivers. And there’s a formal economy there too; that many trucks must mean a great deal of mechanic and other related jobs. If we suddenly converted to electric rail transport, as the green pigeon loving me would like, what would happen to these jobs? My sustainable mobility colleague, Prian Reddy, has a quick rebuttal; “Investment in South Africa’s freight rail infrastructure network will unlock economic opportunities to create well paid skilled jobs in the fabrication of rail train sets, rolling stock and system maintenance. This is in addition to social and environmental benefits of reduced air pollution, traffic congestion, GHG emissions and damage to road infrastructure.”

Supporting green innovation, which will also promote job creation, is where there is work to do. GreenCape has already embarked on this. Three years ago, in partnership with the European Union, GreenCape established the Active Climate Change Citizenship for a Just Transition in South Africa project; designed to empower, in particular, youth, women and under-represented communities, to take up the range of job opportunities that are expected to be in demand as our economy inevitably shifts towards a renewables-based one. Every year this project works with school children to create the “Green Opportunities Challenge”; enabling them to imagine ways they could improve the livelihoods of their communities through renewable energy and other green interventions.

GreenCape also runs, in partnership with the Friedrich Naumann Foundation, an annual “Green Pitch Challenge”; a shark-tank styled pitching competition that brings emerging innovative green small-, medium- & micro-sized enterprises (SMMEs) into a room with investors and incubators. Through these challenges, which have run since 2018, 52 green SMMEs have had the chance to promote their innovations or service offerings, with many going on to scale as a consequence.

Last year, in partnership with GreenCape and the Partnering for Accelerated Climate Transitions (UK Pact) programme, the Mpumalanga Green Cluster Agency launched an equivalent challenge, but specifically targeted at Mpumalanga-based green SMMEs (see here).

One such example is Solar Rais, an Energy-as-a-Service company that owns and operates virtual power plants across Africa. Solar Rais has launched the Women for Green Jobs (W4GJ) programme, a groundbreaking initiative aimed at empowering unemployed female youth in South Africa by creating 50 jobs in the renewable energy e-mobility sector. E-mobility for sustainable development goals means fossil-fuel free transportation across land, water and air.

So where is the ICN in all of this?

GreenCape works towards decentralized solutions to our economic and societal challenges. Not only does this approach create more jobs, but it also appears to be the most efficient way for dealing with the urgent service delivery needs of our most impoverished communities. Supporting green SMMEs is therefore critical, as these organisations are developing the innovations required to tackle these challenges.

Clusters create ecosystems of support. Through the ICN, which links green clusters across the world, the competitive development of the SMMEs connected to their clusters can be enhanced. A key ICN objective is to ‘accelerate the adoption of cleantech’ globally. By enabling a network of green clusters, and strengthening them, the ICN is creating the environment to support the abnormal growth of green SMMEs linked to the network.

One of the takeaways from the conference was a resolution to create an ICN global green pitch challenge. This will see the best green SMMEs from across the globe getting access to a global platform. For these organisations, this will mean a shift from local credibility to global relevance; and the implications therein are significant.

The traffic cop had told me not to rush to where I was going, but to do so the right way. Extrapolating that analogy to the Just Transition, I’m struck by the realization that through organisations like GreenCape, and bodies like the ICN, the approach is to direct our transition towards the green opportunities that are mushrooming all over the world. If that isn’t enough of a reason, then surely cleaner air and better roads make for a great additional caveat?

A blog by Nicholas Fordyce, Communications & Publications Manager at GreenCape.